We’ve talked about fats and carbohydrates (part 1 and part 2) already, but what about protein?

Like the other macronutrients, protein can be misunderstood.

Like dietary fat, I’ve heard from people including trainers that protein can make you fat if you consume too much. Let’s be clear – too many calories can lead to fat gain, not necessarily any one specific macronutrient. However, with that in mind, we need to be thoughtful about what is paired together with protein as well as how protein is utilized in the body. Is eating a whole egg really a problem, or is it that many people won’t just eat one or two yolks, but will pair the meal with buttered toast, multiple pieces of fatty bacon and top it all with salt? While these components may not always be the “healthiest” choice, individually they can be fine in moderation, but together – it’s like a league of villains, or can be if they are consumed too often.

Ok, so what is protein?

Chemically, protein is a polypeptide of 50 or more amino acids that have biological activity. Protein is found in our DNA, which means it is found in our muscle mass, blood, bones and skin. “They function in metabolism, immunity, fluid balance, and nutrient transport, and in certain circumstance they can provide energy (Timberlake, Karen, 2018).”

Nutritionally, we know that one gram of protein has four calories associated with it. We know that protein needs are lower in comparison to carbohydrates and fats because the body utilizes carbohydrates as a first line of energy followed by fat (Thompson & Manore, 2015). This doesn’t mean that protein isn’t important. Dietary protein helps us conduct daily business. It helps the body to function without depleting protein found in the body (i.e. muscle mass).

But, you can consume too much protein and we will get to that, but first some background.

In chemistry, protein is called a polypeptide, which a chain of amino acids.

Amino acids are called building blocks because they are single units that bond together to make protein.

There are 20 amino acids found in our bodies (Timberlake, Karen, 2018). We can make 11 of them, but there’s another nine that we need to get with our diet. Amino acids that must be consumed are called essential amino acids. They’re essential because without them our bodies can’t make other proteins for other body functions like neurotransmitters. The 11 amino acids we can make are called nonessential amino acids.

- Alanine

- Arginine

- Asparagine

- Aspartate

- Cysteine

- Glutamate

- Glutamine

- Glycine

- Histidine*

- Isoleucine*

- Leucine*

- Lysine*

- Methionine*

- Phenylalanine*

- Proline

- Serine

- Threonine*

- Tryptophan*

- Tyrosine

- Valine*

*essential amino acids

I’m sure many of you have heard of BCAA’s or branched chain amino acids. You’ve probably seen them in the store in a pill or powdered form. Simply, these are specific amino acids that have a branch. They can assist in decreasing protein synthesis, which means they can help prevent muscle breakdown and losses, however, there isn’t much research the proves this to be true or consistent (Wolfe, 2017). There are three BCAA’s out of the nine essential amino acids: leucine, isoleucine and valine.

I’ve heard people say that amino acids are inferior to protein. You can’t confused BCAA’s with all amino acids. I would say that drinking or consuming a BCAA if you recognize deficits or holes in your nutrition can be helpful, however, I would recommend that you eat a complete protein rather than drink amino acids or a protein shake. But – remember, it’s also about preference too – drinking BCAA’s won’t hurt you and some people just like protein shakes. I’ve tried BCAA’s, but I never noticed a difference and that could be because of dietary diversity even when in a caloric deficit.

Moving on.

So an amino acid is equal to a single unit, protein is equal to many units of amino acids. As you can imagine, there are many combinations of amino acids and the combination determines the function of the protein in our bodies.

Here are some things in our bodies made up of amino acids:

- endorphins

- hemoglobin

- collagen

- insulin

- enzymes

- muscle

Above, I mentioned complete protein. A complete protein has all of the essential amino acids in it.

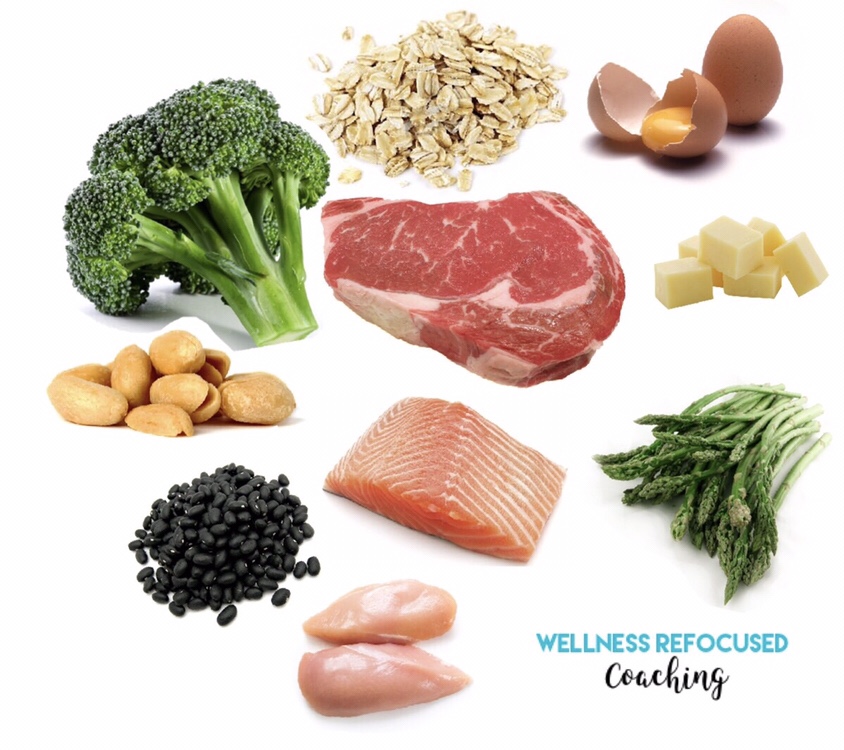

Examples of complete proteins:

- egg whites

- meat

- poultry

- fish

- milk

An incomplete protein lacks one or more essential amino acids.

Examples of incomplete proteins:

- corn – missing lysine and tryptophan

- beans – missing methionine and tryptophan

- almonds and walnuts – missing lysine and tryptophan

- peas and peanuts – missing methionine

- wheat, rice and oats – missing lysine

Dietary protein helps us build our bodies (Thompson & Manore, 2015). Our bodies are resilient and function smartly. When protein is broken down in the body, the amino acids are recycled into new proteins. Like mentioned above, protein helps with hormone balance, fluid and electrolyte balance, repairs our bodies and helps us grow, but as an energy source our needs are pretty low. This is due in part because we recycle amino acids because our bodies don’t have a “specialized storage form” of protein.

So how much should you eat?

At one point, the recommended daily allowance (RDA) suggested .8g per kilogram body weight per day for both inactive and active individuals. However, more research has shown that individuals who are active may need more. The ranges should vary based on a number of factors such as gender, age, size, but also the kind of activity you do, which is where I slightly disagree with the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. A 2009 review of these guidelines determined the following concepts:

- protein is a critical part of the adult diet

- protein needs are proportional to body weight; NOT energy intake

- adult protein utilization is a function of intake at individual meals

- most adults benefit from protein intakes above the minimum RDA

They examined current perceptions about protein as well as benefits to treat and prevent obesity since 35.7% of U.S. adults were considered obese and 16.9% of U.S. children and adolescents were obese at the time of the review. The most recent NHANES data from 2013-2014 shows that 38% of adults are obese with 19% of children and adolescents being obese. A major flaw pointed out by this review highlighted the proportion of protein to carbohydrates and fats may be adequate with high energy consumption, but that as “total daily energy intake is often below 1400 kcal/day” when individuals seek to lose weight it could be potentially harmful to limit protein needs to the RDA as a loss in lean muscle mass could result (Layman, 2009).

In 2011, a study looking at required and optimal amounts of dietary protein for athletes found that while the RDA was .8g per kilogram, it was would be appropriate for athletes, both endurance (distance runners) and strength (bodybuilding and weightlifting) to consume between 1.6 to 2.25 times the RDA or 1.2g to 1.8g per kilogram (Phillips & Van Loon, 2011). The study also suggested that protein consumption between 1.8 to 2.0 per kilogram could be helpful depending on caloric deficit for the preservation of lean muscle mass.

Now, remember this study looked at protein consumption for very active people.

If you’re sedentary, there’s no reason to consume as much as an athlete. If you are active, you may also need to consider how much potential lean muscle mass you have. If you’re overweight or obese, your protein needs may be less.

I formerly had a client who was consuming 1g per pound she weighed and it was over 200g of protein because a former coach had recommended it. She had an equal amount of protein to carbohydrates, which is a common calculation, but necessary.

A 1:1 ratio of protein to weight in pounds is a common suggestion and it’s one that I utilized when I first started tracking macros, but as I started looking at my specific goals and needs, I realized what I was consuming wasn’t helping me and I redistributed my nutrient goals.

While this client was very active and participated in weightlifting multiple times a week this 1:1 ratio of protein was inappropriate for her because it wasn’t taking into consideration lean mass, but instead overall mass. It also left her feeling bloated, hungry and often with disproportionate nutrients to be satisfied.

So what can happen if you consume too much protein?

There are a few health conditions that have raised concerns, but they may not impact everyone – there’s also some contradictory research and you need to figure out what side of the fence you’re on.

Concerns around heart disease and high protein consumption also involve high amounts of saturated fat found in animal products (Thompson & Manore, 2015).”. High saturated fat levels have been know to increase blood cholesterol levels and increase risk for heart disease. However, a moderate protein diet that is low in saturated fat can be good for the heart. Again, this is correlation, not necessarily causation.

Another concern is that excess protein found in the urine due to kidney impairment. “As a consequence, eating too much protein results in the removal and excretion of the nitrogen in the urine and the use of the remaining components for energy (Thompson & Manore, 2015).”

When protein is found in the urine it’s called proteinuria. As part of the body’s fitration system, kidneys remove waste from your blood, but allow nutrients like protein to return to the bloodstream to be recycled through the body. Protein in your urine can be a sign of impaired kidney function. It’s important to note there is no evidence that more protein causes kidney disease in healthy people that aren’t susceptible to the disease, however, more water should be consumed to flush out the kidneys because of protein metabolism (Thompson & Manore, 2015).

Bloating is also possible if “too much” protein is consumed in one meal and your body doesn’t produce enough enzymes to assist in digestion. Chemical protein digestion occurs in the small intestine as a result from the enzyme pepsin. “Too much” is relative. I get bloated if I have more than 40g of protein in a meal. Depending on planning I can prevent too much consumption, but that’s not always the case.

Like mentioned above, athlete and highly active individuals may need more than the RDA, but the average person may not need as much. Much recent research I found that examines the impacts of high protein consumption utilizes athletic bodies in high resistance training settings, which isn’t necessarily a sample that will provide data that can be used for recommendations for an inactive or lightly active person.

The data is still interesting, but may not be helpful to the average person.

When I did find research articles discussing higher protein needs in obese individuals, I found many studies designed diet plans for participants with sub-1000 kcal/day. This is an extreme diet that may not typically be suggested for one to conduct without being monitored. An example of this extreme design is a study published in 2015 that examined normal protein intake versus high protein intake as well as carbohydrate reduction to determine success in weight loss and maintenance. Researchers assigned adult participants to 800 kcal/day for eight weeks and once participants had an 11 kg loss they randomly assigned them to a new plan with varying protein intake for six months. They found that individuals with higher protein intake were able to adhere to the plan, which not only resulted body fat losses, less inflammation and better blood lipid panels, but also were capable of maintaining losses. Researchers also suggested that less restrictive approaches also lead to higher adherence (Astrup, Raben, & Geiker, 2015).

Again, interesting, but this is an extreme that hopefully many won’t use or need.

What about if you eat too little?

While we don’t need as much protein for energy as many believe, we do need dietary protein to assist in building our bodies like mentioned above. Without dietary protein, our bodies breakdown stored protein i.e. muscle to be utilized to assist in daily functions such as creating amino acids. A true deficit of protein can result in a greater number of infections if the body is unable to produce enough antibodies. A true deficit occurs over time and in extreme circumstances; however, can be more likely if an individual is in a large caloric deficit.

So, easy question- what food sources have protein in them?

Obviously meat is an excellent protein source, but there’s more than meat. Legumes like lentils, black beans and green peas as well as nuts have protein in them too. While oatmeal is a well-known grain, it also has about 5g of protein per half cup serving. Dairy, while also another carbohydrate source, is also an excellent source of protein and the mineral calcium – if you’re not lactose intolerant!

Vegetables that have protein in them that I recommend to clients who are trying to balance out density and volume in their eating include broccoli, Brussels sprouts and asparagus.

Like the other macronutrients, protein can be flexible within reason. Considering multiple factors to determine a specific plan for you will be key. It might take trial and error, it may also take some adjustments, but give yourself time.

Your nutrition should be specific to you and your goals. It should take all of you into consideration like have you approached menopause or had a hysterectomy? Hormones play a huge role in overall nutritional needs. What’s your sleep like? Are you on medications? What’s your stress like? Are you sitting more or less than before?

I know many of these questions can seem silly when posed, but they are important.

The body is a weird organism, just when we think we have it figured it out, it changes on us.

References:

Layman, D. K. (2009). Dietary Guidelines should reflect new understandings about adult protein needs. Nutrition and Metabolism, 6-12.

Phillips, S., & Van Loon, L. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Science, 29-38.

Thompson, J., & Manore, M. (2015). Nutrition: An Applied Approach. San Francisco: Pearson Education.

Timberlake, Karen. (2018). Amino Acids, Proteins and Enzymes. In K. Timberlake, Chemistry: An introduction to general, organic, and biological chemistry (pp. 548-583). New York: Pearson.

Wolfe, R. R. (2017). Branched-chain amino acids and muscle protein synthesis in humans: myth or reality? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14-30.

1 thought on “Wellness Refocused Education: Protein and Amino Acids”

Comments are closed.